Teach progress, not pessimism.

The way we're teaching history is turning our children into cynics. Here's how to change it.

Optimism has become a lost art.

So few of us are idealistic about the future — and it’s starting to rub off on our kids.

Teenagers used to see the world as their oyster. Now, 44% of them feel sad and hopeless.

The rising generation doesn’t even expect to reach old age, because the state of the planet feels too precarious.

This cynicism isn’t just a teenage phase — it’s not normal. It’s a sign that something is deeply, deeply wrong.

And it’s a sign that we desperately need a new way of seeing the world, one that cultivates hope and optimism in our kids.

How else will they summon the courage to face the crises of our age?

Here’s how we can show them the light:

History — the study of human progress

History is storytelling. The stories we tell our kids about how humanity arrived at the present day shape how they see the world (and subsequently, the future).

In other words, how we teach history matters.

And it’s why education today feels something like a battleground:

Should we teach kids a version of history that focuses on the horrors of our past, painting a picture of humanity as fundamentally flawed (resulting in pessimistic kids)?

Or should we teach a version of history where negative events are not taught at all (creating a generation of students ignorant of the past and afraid of the truth)?

Dr. Maria Montessori opted for a third option.

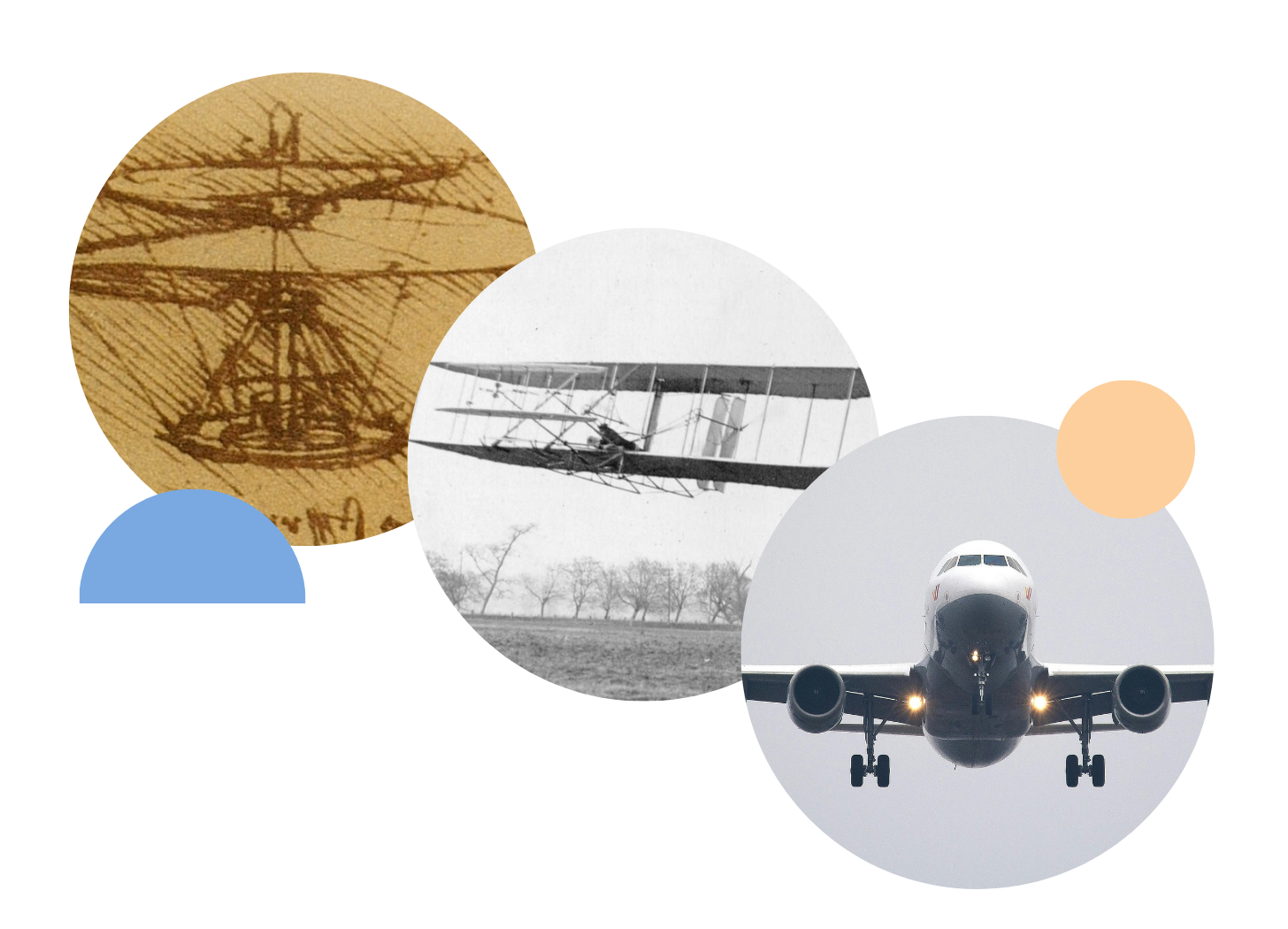

Montessori taught history as a study of human progress:

All the beautiful things humanity has created, and

All the terrible things we have overcome.

It’s the kind of awe that comes from realizing that we sent a man to the moon with less technological power than we now hold in our hands every day.

But it’s not just a study of all the famous people we remember reading about in our history books.

It is also an appreciation of the anonymous sacrifices of people who will never “go down in history,” but who nevertheless worked to advance civilization.

In her words:

“Let us in education always call the attention of children to the hosts of men and women who are hidden from the light of fame, so kindling a love of humanity.”

Studying history through the lens of human creations and inventions is how we raise children who love humanity — because they can appreciate and acknowledge the beauty of human creation.

Montessori didn’t believe that encouraging a love for humanity and learning about the horrors of the past were mutually exclusive.

Her framing of history was not a sanitized, whitewashed version. Telling children the truth about the past isn’t what is making them depressed.

It’s that we often leave out the other part of the story — which is a lot of good.

Montessori herself lived through two world wars and was exiled from Italy in the 1920s for refusing to turn children into soldiers. She knew a thing or two about hard times — but she wasn’t cynical.

“Think how many things man has created,” she said. “We must put the creations of man at the center, and not his defects.”

Montessori’s philosophy goes beyond history class — it is a centering of human greatness that permeates every subject, from literature to science.

Nothing will make you more optimistic about the future than studying, for example, the history of science (a little over a century ago, we were still leeching people who had fevers and gout. Look how far we’ve come!).

We will always have reasons to feel cynical about our fellow man (and to teach our children to feel the same).

But when we intentionally take note of human progress, we open our hearts again. Montessori knew this and made it a key component of her work.

Why hope is vital

Children shouldn’t be cynical about the state of the world.

It doesn’t just harm their development — it halts human progress.

“For an effort in any given direction to take place, the world has to be seen… as malleable, problems seen as a set of engineering challenges to be overcome by human ingenuity,” says Lea Degen, an Emergent Ventures Fellow and undergraduate.

Rather than treating history as a review of humanity’s greatest catastrophes, we should focus on what we have overcome.

As a result, we will teach children to see themselves as the next in a long line of changemakers and problem solvers.

Despite massive advances in STEM over the last century, we take much of our progress for granted — something Montessori warned against.

“[Montessori] worried that we’ll fail to appreciate the inventions, achievements, and creations of civilization,” says Matt Bateman.

In her own words, “... humankind should feel itself king of all that has been created, transformer of the earth, builder of a new nature, collaborator in the universal work of creation.”

By teaching progress, by shining a light on the greatness of humankind, we give our children something to be grateful for, as well as something to feel hopeful about.

This is how we raise optimistic adults.

And when the rising generation feels hopeful about the future, they’re poised to bring about the next wave of progress.

If you have a high school student (or know one who would benefit from this approach to history education), check out our online course Progress Studies for Young Scholars.

☀️ This week’s bright spots:

If you have 1 minute…

Watch a video about Montessori-inspired items you can find at Target.

If you have 5 minutes…

Read this tweet thread from Samantha on why Montessori is so different from the mainstream.

If you have 10 minutes…

Read this article by Simon Sarris on why school is not enough.

I believe we must teach historical facts with honesty. That honesty does not mean that we sink into doom and gloom. All of us, and especially our young people need to remember the equally honest facts about our human accomplishments and achievements. We need to challenge these kids to see themselves as problem solvers.